The Boys is a 2019 Amazon Prime television series created by Eric Kripke. It takes place in an alternate universe, in an America that is overrun with superheroes. These heroes are all operating under the thumb of the overbearing Vought Corporation, whose main commodity is an elite super squad called The Seven.

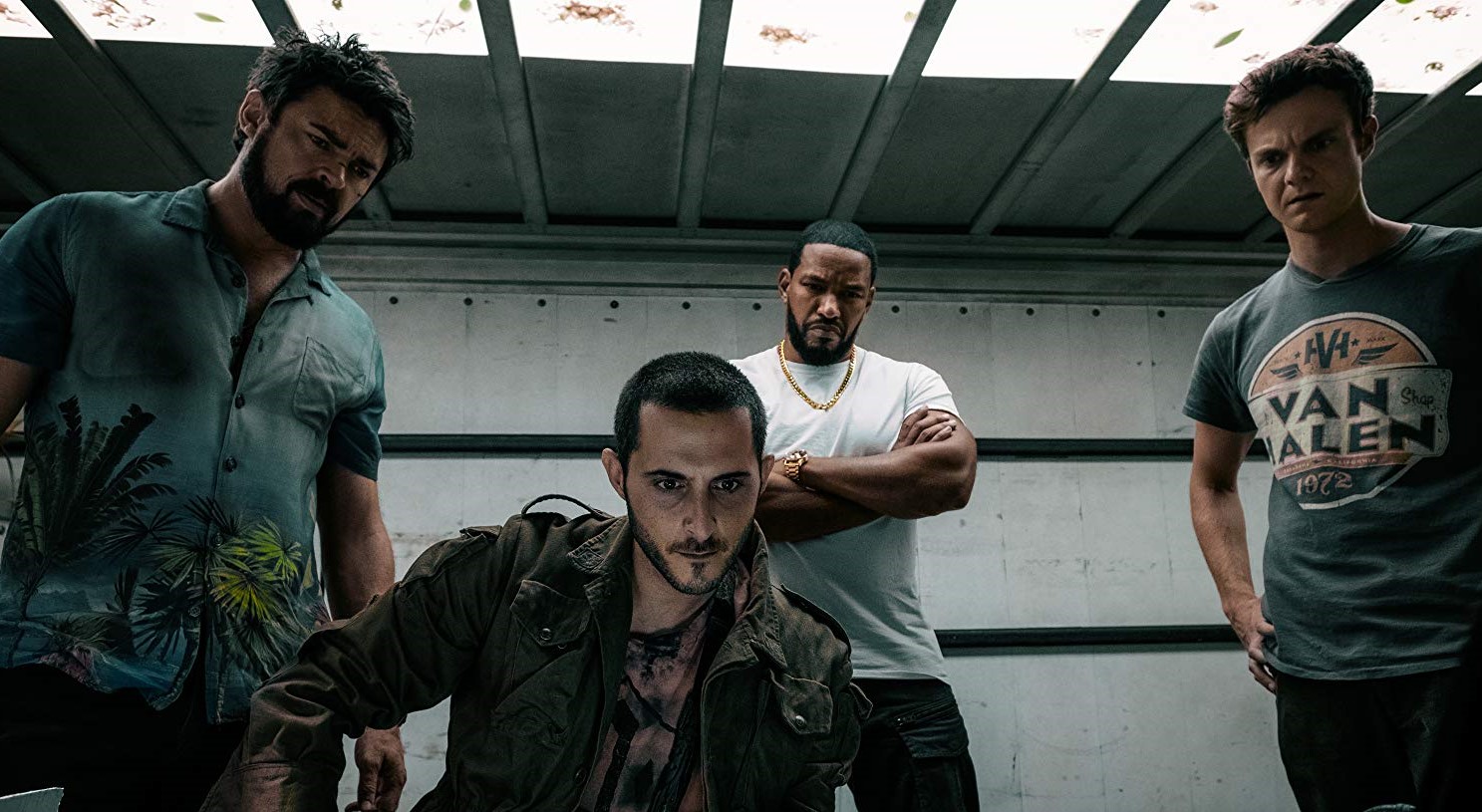

Meanwhile, Hughie Campbell (played by Jack Quaid) suffers a tragic loss, and is thrust into a world of intrigue and espionage when he meets Billy Butcher (Karl Urban). Hughie finds himself at the center of a vast conspiracy, pitted against the all-powerful superheroes he had once admired, in his quest for the truth. And once someone is an enemy of The Seven, there’s no turning back.

Before we get started, this review is neither intended as a judgement nor an accusation of the fans of the show. Instead, I am hoping to shine a light on some of its more questionable and unsettling aspects. Many people really enjoyed it, and I can see why. It’s got an interesting concept, great acting, beautiful set design, and lots of dramatic twists and turns.

It was obviously designed to be controversial and uncomfortable to watch, and I do understand that this is a valid artistic choice. That said, I think The Boys fails in its attempts at commentary and ultimately does more harm than good. If you want to learn why, please read on.

The Superhero Conundrum

On the surface, The Boys is a harsh critique of America’s status quo. The show seems to have a comment for every current, hot-button issue. It covers sexual harassment, drug addiction, lobbying, weaponized faith, corporate commodification, terrorism, media sensationalism, vigilantism, and of course, blind hero worship.

All of these topics are worthy of discussion, and many lend themselves well to the superhero genre, especially in our current politically-charged climate.

Why do we seek comfort in these larger-than-life vigilantes? Why don’t we insist that our heroes abide by our laws? What drives us to worship at the Altar of Might? And most importantly, do superheroes actually work on behalf of the people they claim to protect?

A History of Complicated Morality

By definition, superheroes have a complicated relationship with law and order, and this often lands our favorite Spandex-clad crusaders in morally grey territory. Batman has no problem with illegal extradition in The Dark Knight, nor does he have any qualms about illegally tapping thousands of phones. In Man of Steel, Superman reduces the city of Metropolis to rubble in an attempt to catch a single terrorist. S.H.I.E.L.D. (the Strategic Homeland Intervention, Enforcement and Logistics Division) regularly operates outside of its jurisdiction. Captain America and Scarlet Witch spend the first sequence of Civil War running black ops in the middle of the day on a crowded street in Nigeria.

The list goes on and on. It’s almost comical. Our superheroes are traipsing around the globe, blowing up bad guys, and making pithy jokes all the while like they’re Team America: World Police.

Yes, many of these films bring up the possibility of government oversight, but none of them actually dig deep into those murky waters. Frankly, that would be bad for business. In order to sell superheroes to the public, these movies MUST regularly reinforce the message that the ends justify the means.

The writers of The Boys saw these things. What they saw made them angry. So what do they actually have to say about it? It turns out: very little.

The Message

The very first episode places sexual harassment front and center. A woman is terrorized and threatened by one of her male coworkers. She finds the strength within herself to finally fight back, returns to the boardroom, confident, head held high, and proceeds to do ABSOLUTELY NOTHING. The woman never takes her harasser to task. She doesn’t even attempt to file a complaint. She suffers in silence. What does The Boys have to say about sexual harassment? It’s bad.

Commodification and lobbying are the biggest targets of the show’s ire. In The Boys, corporate ideology is personified by Madelyn Stillwell, played by Elisabeth Shue. She speaks at shareholder meetings, brushes elbows with congress, covers up scandals, and manages Vought’s most lucrative superhero account, Homelander. Even though she knows that The Seven are not good people, she has no ethical qualms about it.

She sells an image, a dream, a product that can be bought and sold. I waited the entire run time of season one to learn her motivations and unravel her dark plans. But, there are no dark plans. She wants to sell her superheroes to the armed forces. That’s it. What does The Boys have to say about commodification and lobbying? It’s bad.

Why So Cynical?

This happens over and over and over again. Concepts are introduced but never explored. Believe Expo? It’s bad. Compound V? It’s bad. The Seven? They’re bad. The show doesn’t have anything to say about weaponized faith or drug addiction, and there’s nothing sympathetic about The Seven. They’re one-dimensional cartoon villains. There’s no complexity here, and without complexity, the show fails to reflect anything real about society.

The Boys is a harsh judge, constantly bombarding its viewers with thinly-veiled rants about religious hypocrisy, evil corporations, herd mentality, and ineffective government; but when it comes to actually SAYING anything about these issues, it’s remarkably quiet. The Boys is not a discussion. It’s a grandiose, self-congratulatory thesis on all of the ways that everything is bad.

There are a lot of problems with characterization, framing, and tone, which only serves to further undermine its supposed themes. Let’s dig into just a few of these issues.

Be warned, from here on out, there will be plenty of spoilers ahead. If you’ve already seen the show, or if you’re not planning to watch it, feel free to read on.

The Problem with Starlight

Starlight is a Cardboard Pixie Dream Girl. Her character is full of contradictions that make her attractive to a very specific type of person. She is beautiful, but she doesn’t like to draw attention to herself. Despite having super strength and agility, she lets her date win at bowling. While she enjoys sex, she acts like a virgin. She is Christian, but only in a casual way. While she seems strong and independent, she’s also endearingly insecure. She makes impassioned speeches, but she doesn’t DO anything.

It’s unfortunate. Her character had a lot of potential. How would a strong, driven superwoman fare in a toxic, male-dominated workplace? Would she fight for justice from within the system, or would she go rogue? How would she handle her disappointment and disillusionment? How would she keep hope alive?

We’ll never know. Starlight’s screen time is dominated by her relationship with Hughie. Her final, anticlimactic showdown is with A-Train, one of the few Supers with whom she has zero conflict. She doesn’t confront Queen Maeve, Homelander, The Deep, or even Stillwell. This is Hughie’s story, and she’s just along for the ride.

This lack of character development makes her sexual harassment subplot feel cheap. Such sensitive subject matter requires a certain level of trust from the audience, but The Boys has no interest in building that trust. It blindly flails its way through an uncomfortable and disingenuous scene. One which reeks of a meeting where the writers might have noted that the “Me Too” movement is really in right now. The Boys treats women like little more than a demographic, and I, for one, don’t like being pandered to.

The Problem with The Deep

The Deep loses his cushy job, is kind of a joke, and his plans are constantly thwarted by his own ineptitude. I don’t feel sorry for him. When a woman shoves her hands in his gills, he gets a taste of his own medicine. I don’t feel sorry for him. He shaves his head and gazes, forlorn, at his reflection in the mirror. Yet I still don’t feel sorry for him.

After sexually harassing his coworker and threatening to get her fired if she talked, his only punishment is being forced to relocate to Ohio. Seriously. That’s it. Not a single repercussion. The writers seem to think that forcing this character to endure sexual assault should satisfy the audience, but the effect is immediately undermined by his lack of a character arc. Even after that encounter, he never shows genuine remorse for his actions. I don’t want to see him suffer. I want to see him change. In the end, The Deep is pitiable, but for all the wrong reasons. He is an abuser, and his suffering doesn’t change that fact.

This leads me to question the motivations behind the use of “Everybody Hurts” by R.E.M. during such an important sequence. If the song is meant to encourage empathy for The Deep, then it fails because the lyrics are reduced to their most simplistic meaning. Yes, obviously, everybody hurts sometimes. Even abusers. That doesn’t make them less abusive and abhorrent. If the song is meant as a joke (as it so often is), then it’s a cruel attempt at humor. “Everybody Hurts” is, first and foremost, about suicide prevention, which is no laughing matter. Either way, the choice of song is utterly tone deaf and demonstrates The Boys‘ inability to discuss these touchy topics with any subtlety or insight.

The Problem with Billy Butcher

I knew that I was in for a rough ride when Billy Butcher was introduced with an un-ironic monologue about how we don’t shake our babies enough. Butcher is all over the place as a character. He’s a former CIA agent, murderer, a laid-back, cool dude, while also being a rebel, villain, antihero, and a loose cannon.

Butcher is the kind of character that looks great on paper. He’s got cool one-liners, a tragic backstory, and a devil-may-care attitude. He’s an amalgamation of every cool guy anarchist trope. The intention was probably to evoke other beloved comic book antiheroes, like Fox from Wanted or V from V for Vendetta. What we actually got was Tyler Durden.

Yes, Tyler Durden, the renegade leader of the space monkey army. Fight Club is a fantastic movie and an engaging book, and Tyler Durden is a fascinating character study. He’s a male power fantasy: a lover and a fighter; a warrior poet with a penchant for destruction. He doesn’t play by our rules. He makes his own rules. Karl Urban as Billy Butcher (in an admittedly brilliant performance) owns Tyler Durden’s trademark stench of Hawaiian shirts and menace.

The Truth About Tyler Durden

Here’s the problem: Tyler Durden, the ultimate male symbol of power, is a joke. Fight Club was published in 1996 by, then unknown, author and underground queer icon, Chuck Palahniuk. The author of Fight Club is a gay man, and this is vital to understanding the subtext of the story.

Fight Club isn’t about taking back male power or fighting the system. It’s about self-loathing. It’s about the toxic stereotypes that we force ourselves into to conform with societal expectations. Tyler Durden is the worst kind of fantasy. He’s a projection of everything the narrator thinks he’s supposed to be. Therefore, the narrator has to destroy him in order to accept himself as he truly is. That’s why he’s the villain.

The writers and directors of The Boys either didn’t understand this irony or didn’t care. Butcher is an absolute psychopath, and not in a fun way. The show, for some inexplicable reason, refuses to frame Butcher as the villain of the piece, despite all signs pointing in that direction. If the writers thought they were giving us a compelling anti-hero, they missed the mark by about a mile.

The Problem with Hughie

Hughie is a typical self-insert protagonist. He’s just a regular dude who happens to find himself in a perilous situation, surrounded by larger-than-life characters, like Bella Swan or Frodo Baggins.

Except that he’s not. Frodo is kind and compassionate, flawed but loyal, and truly cares for his family and friends. Meanwhile, Bella may not have the traits of a hero, but she does have a personality. There’s no question about what motivates her. She wants Edward.

Meanwhile, Hughie doesn’t seem to want anything. At first, it seems like he will be motivated by the tragic death of his girlfriend, but by the end of the third episode, that thread is all but forgotten. There are some episodes, like “Good for the Soul”, where he is entirely disengaged from his surroundings. Whenever Butcher asks him to do something morally reprehensible, he hems and haws, frowns and shrugs, and then gives in. Hughie wields apathy like a shield to protect him from judgement. He didn’t want to do the evil thing. He had to.

The Boys doesn’t have any time for emotional and moral complexity. Hughie is the hero, and the show frames him that way. His actions are always justified in the long run. Did he murder Translucent in cold blood? Yes, but that guy was a jerk. Did he use his romantic relationship with Starlight to blackmail a fraudulent preacher by falsely claiming that they’d had anonymous gay sex? Sure, but that gave them the information they needed to track down Compound V. But wouldn’t it be more interesting if his actions WEREN’T vindicated? If the ends didn’t actually justify the means?

A Missed Opportunity

My biggest problem with Hughie is that the show came so close to getting it right. After the first episode, I was excited to see how his character would change and develop. I thought we were finally getting The Incredibles, but from Syndrome’s point of view.

Syndrome is a compelling villain, and he’s arguably one of the most sympathetic bad guys in superhero lore. How fascinating would it be for the audience to grow to care for Hughie, and then watch him slowly become the monster that he’s so desperate to defeat? It’s all right there in the first episode, ripe for the picking. Unfortunately, they never explore this concept.

When A-Train takes Hughie’s father hostage, Hughie breaks A-Train’s leg and then… leaves him there. In another show, this may have been a great moment of character growth, but not here. Hughie doesn’t spare A-Train out of pity or empathy. Instead, he leaves A-Train because the plot needs him to be somewhere else. A-Train hunts Hughie down, but shouldn’t it be the other way around? Why isn’t Hughie trying to destroy the now-weakened A-Train? Why is A-Train the driving force for this plot instead of Hughie?

Mainly because Hughie doesn’t actually stand for anything. He’s an empty shell, stuffed to the brim with condescension, mild irritation, and self-righteousness.

The Moment that Defied All Reason

In the penultimate episode, “The Self-Preservation Society”, Starlight finally reaches out to Hughie to demand an explanation for his deception, and the two lovers agree to meet at their park bench. When she rightfully confronts him and calls him a liar and a murderer, Hughie, of course, responds that he didn’t have a choice. Starlight doesn’t accept this weak excuse and decides to take Hughie to the police to answer for his crimes.

In a desperate attempt to save his own life, Hughie tells Starlight the terrible truth: her superpowers are manufactured. She was injected with Compound V as a baby. Her powers aren’t a “Gift from God.” Starlight hesitates, and then a red dot appears on her chest.

Enter Billy Butcher, casually toting an AR-15 in a crowded park in the middle of the day. He points the gun at her chest and fires. Starlight goes down. The innocent civilians start screaming and running in all directions as Butcher yells to Hughie to run. Then he takes aim and fires again.

Hughie looks down at the innocent young woman lying on the ground at his feet, the woman who saved him from his self-destructive grief, who gave him every bit of herself. They’d made love only a few days before. He looks down at her and says, “I’m sorry.”

AND THEN HE LEAVES HER THERE. He runs away, leaving the woman he presumably loves to bleed on the ground. “I didn’t ask for your help,” he chides Butcher, as they make their escape. This is our protagonist, folks. This selfish, neurotic, spineless little twerp is our hero.

The Fallout

Yes, Starlight is a superhero; she can withstand a few bullets. But Hughie doesn’t know that. He’s only ever seen her super strength and light-up eyes.

Because the park sequence is the cliffhanger for the season finale, the audience is left to ponder the possible fallout from this horrible string of events. How will they resolve this conflict in the next episode?

They don’t. In fact, nobody ever mentions it again. What follows instead is an unbearable onslaught of blatantly open ends. Hughie never demands an explanation from Butcher. Frenchie never pulls Butcher aside to say, “Hey, maybe it wasn’t a good idea to gun down a Super in a crowded park in broad daylight.”

Most insulting of all, when Starlight gets her chance to confront Hughie, she chooses to berate him for revealing the truth about her superpowers. She never mentions that Hughie’s friend shot her, twice. It never comes up that he LEFT HER THERE TO DIE. That’s not just insulting to Starlight’s paper-thin veneer of narrative agency. It’s also just plain bad storytelling. Actions should have consequences. It’s Writing 101.

In the end, Starlight decides to join forces with Hughie because he gives her a speech about how it’s the “right thing to do.” Hughie wouldn’t know the right thing to do if it slapped him in the face. He’s a garbage person, and Starlight is just a pretty prop.

What To Do Instead of Watching The Boys

The Boys is cynical, and it puts reprehensible behavior on a pedestal. I do not recommend it. Instead, here are some other interesting takes on the superhero genre.

Did you like the message about the commodification of superheroes in a late capitalist dystopia? Try Mystery Men. Captain Amazing, played by Greg Kinnear, is a loving, but surprisingly harsh, send-up of America’s favorite superhero. Crowds of admirers and journalists flock around him as he praises the efforts of common people, a perfect image of honor and humility. Meanwhile, in private, he prattles on about his Pepsi endorsement and complains that there aren’t enough supervillains to fight. Sound familiar?

Or maybe you liked the gritty portrayal of superheroes as uninspired, jaded narcissists. Then Watchmen by Alan Moore might be for you! Or watch Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog. Captain Hammer is just the worst in the most delicious way. He’s a singing buffoon played by the world’s most lovable ham, Nathan Fillion, and yet, he’s way less of a cartoon villain than Homelander is.

Did you like seeing tired superhero tropes taken in new and unexpected directions? Watch Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse. It’s sleek and fun and unbelievably well-crafted. One Punch Man is an imaginative, beautifully drawn subversion of traditional superhero and anime tropes. Both of them are streaming on Netflix (at the time of writing this). Or you could watch Unbreakable or Megamind or Hellboy or Batman: Mask of the Phantasm. Even Chronicle would do in a pinch. But don’t watch this overblown, self-important, vitriol-spewing show. There are so many better things you could be doing with your time.

The Boys: Final Thoughts

The Boys is the kind of show that could only be made in 2019. It’s riding a wave of loud, but unhelpful, disaffected armchair anarchism. While it attempts to cast judgement on religious extremists and corporate pandering, The Boys actually serves as an accidental condemnation of the detached apathy we’re seeing far too often these days. Is this shallow, cynical, hateful escapism really what we’ve been reduced to? I hope not. Hopefully, in five years we will look back on The Boys and scratch our heads, wondering why we ever liked it in the first place.