Brazil is a 1985 film written by Terry Gilliam, Charles McKeown, and Tom Stoppard and directed by Terry Gilliam. It stars Jonathan Pryce as Sam Lowry, a listless upper class bureaucrat who spends his days fantasizing about being a hero and saving the woman of his dreams, Jill. When Sam is offered a promotion, he takes it in the hopes of discovering Jill’s identity and winning her trust. Meanwhile, Sam is plagued by troubles at home, including a mother addicted to plastic surgery and a faulty air conditioning unit that fills his house with noxious gas.

When he finally meets Jill, it is due to a fatal record-keeping error that places them both in opposition to the strict totalitarian government that controls the city. Using only his wits and the resources available at his new middle management job, Sam must finally take his life into his own hands and fight to save the woman he loves.

In this analysis of Brazil, we will discuss Dystopia and The Social Contract.

What is Dystopia?

Dystopia is a storytelling device that can be found in almost all forms of media. Dystopias are especially popular in Young Adult fiction with the likes of The Hunger Games, Divergent, and the Maze Runner series. They are also popular in television with hit shows like The Walking Dead and The Handmaid’s Tale. Our greatest societal fears are often explored in dystopian media: the fear of too much or too little government control, the fear of religious theocracies, the fear of being overthrown by an alien force (earthly or extra-terrestrial), or even, as seen in Idiocracy, the fear that the downfall of humanity will be caused by nothing more than our own stupidity.

Even though dystopias are extremely popular in modern media. The word “dystopia” is a relatively recent addition to the English language, and was only created as an antonym to the word “utopia”. So, to properly define dystopia, we need to understand the meaning of utopia.

Popularized by Thomas More in his 1516 treatise Utopia, a utopia is a society characterized by political or social perfection, resulting in the ultimate happiness of all people. The word “utopia” comes from Greek and literally translates to “nowhere”, emphasizing that such a society does not yet, and may never, exist. Though the book itself depicts a utopia as a governmental structure that we most closely associate with communism or socialism, the term has since been adopted by the popular lexicon to mean any perfect and happy society, no matter how that perfection is achieved. For example, the Garden of Eden, before the fall, is often referred to as a utopia.

A dystopia is the opposite of a utopia. It is an imagined society characterized by a constant state of human misery. In the Western world, dystopias often take the form of an oppressive totalitarian government, though not always. The Mad Max series, for instance, instead builds its dystopia around a crude regime following the fall of traditional government structures; an anarchic dystopia. (This subgenre also tends to pop up in post-apocalyptic narratives.)

The concept of the dystopia has taken hold of our culture, overshadowing the utopia. This is due to its usefulness in discussing topical issues in politics, religion, economics, and society as a whole. Dystopian stories are generally within the domain of science fiction, as the genre lends itself well to creativity and speculation. The Netflix sci-fi show Black Mirror, for example, is comprised almost entirely of dystopian stories.

Brazil was most strongly inspired by George Orwell’s quintessential dystopian classic 1984. However, by Gilliam’s own admission, he’d never actually read the book when he co-wrote the screenplay. Gilliam’s lack of familiarity with the source material makes sense, because while the themes of these two works are very similar, the dystopia in which Brazil is set looks less like Oceania and more like the DMV.

This film’s dystopian government is a bureaucracy. Colloquially, the term “bureaucracy” is ascribed to any industry (government or private) that seems to subsist on complex hierarchies with little regard to merit or effectiveness. Marcy in Human Resources might refer to the Accounting Department as a bureaucracy because they ask her to fill out her forms in triplicate and file them with the acting assistant supervisor, who always seems to be on vacation. For the purposes of this discussion, however, the term bureaucracy will refer to a system of government ruled by administrators and officials and not by elected leaders. This largely amounts to the same conclusion, but it is an important differentiation to make.

Brazil’s bureaucracy is built on the belief that rules and regulations provide safety, comfort, and efficiency; but by taking this concept to its absurd conclusion. Through this, Gilliam shows us the inevitable folly of that line of thinking. Seeking safety and comfort in totalitarian bureaucracy is tempting, but it can never live up to its promise.

The system would be formed and regulated by imperfect humans. In Brazil’s world, you get the sense that citizens are less afraid of Thought Crime and far more frightened by the prospect of committing the most heinous crime of all: making a mistake.

This fear manifests as a desperation for conformity. The citizens conform, not because they fear retribution, but because non-conformity would show them to be a glitch in a perfect system. No one wants to be the broken cog. As Jack Lint says, “Information Transit got the wrong man. I got the right man. The wrong one was delivered to me as the right man. I accepted him on good faith as the right man. Was I wrong?” Jack’s hesitance to accept responsibility for his failures implies a systemic fear of nonconformity and imperfection.

Citizens are terrified that they will be discovered as frauds, despite adhering as perfectly as possible to their designated roles. Their prisons are made of paperwork and red tape and jargon and cold calculation. Brazil grasps a painful fact that very few dystopian stories manage to convey: Totalitarian governments do not spring up of their own accord. The citizens themselves must feed the lie if it is to take hold. Thought Crime is not bad because it is illegal, but because it is UNSEEMLY. However, if one is not free to be unseemly or to make a mistake, then one is not free to improvise or create, to imagine or improve.

In order to understand how a dystopia like this came to be, we must understand the Social Contract and how its violation leads to a constant state of human misery.

What is the Social Contract?

“Any service a citizen can give to the state should be performed as soon as the sovereign demands it; but the sovereign on its side can’t impose upon its subjects any fetters that are useless to the community. Indeed it can’t even want to do so, because there’s no reason for it to want to, and ‘Nothing can happen without a cause’ applies under the law of reason as much as it does under the law of nature. […] The undertakings that bind us to the social body are obligatory only because they go both ways; and their nature is such that in fulfilling them we can’t work for others without working for ourselves.”

-Jean Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract

In short, the Social Contract is an agreement between the Citizen and the State. The details of the agreement and the circumstances vary from philosopher to philosopher, but the gist is that the Citizen willingly gives up some of their rights to the State. In return, the State offers law and order, usually in the form of state-sponsored keepers of the peace (police, military, etc.).

In John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government, he argues that, save for the right to self-preservation, the State should hold all rights to violence:

“Political power, then, I take to be a right of making laws, with penalties of death, and consequently all less penalties for the regulating and preserving of property, and of employing the force of the community in the execution of such laws, and in the defense of the commonwealth from foreign injury, and all this only for the public good. […] This, therefore, contains the power of war and peace, leagues and alliances, and all the transactions with all persons and communities without the commonwealth…”

-John Locke, Second Treatise of Government

This outlook may seem to give the State all of the power, but Locke later amends his statement, giving the Citizen the natural right to overthrow oppressive ruling powers:

“It may be demanded here, what if the executive power, being possessed of the force of the commonwealth, shall make use of that force to hinder the meeting and acting of the legislative, when the original constitution or the public exigencies require it? I say, using force upon the people, without authority, and contrary to the trust put in him that does so, is a state of war with the people, who have a right to reinstate their legislative in the exercise of their power. For having erected a legislative with an intent they should exercise the power of making laws, […] when they are hindered by any force from what is so necessary to the society, and wherein the safety and preservation of the people consists, the people have a right to remove it by force.”

-John Locke, Second Treatise of Government

Locke saw the State as the unified voice of the people, acting of its own accord, but only as a representation of the community as a whole. It was his belief that a government acting within its own designated legislative power, should enact the will of the people and only the will of the people. Also that the people had a right to overthrow a government that failed to enact their will.

Though simplistic in its depiction of the State as a representative of the people (as it does not take into account that the people, not being unified, cannot be properly represented by a single unified force), Locke’s Second Treatise of Government laid the groundwork for the Social Contract that would later be popularized by Jean Jacques Rousseau in The Social Contract.

Rousseau tackles the issues raised by the simplicity of Locke’s Second Treatise with ease. He states:

“For forces to add up in this way, many people have to work together. But each man’s force and liberty are what he chiefly needs for his own survival; so how can he put them into this collective effort without harming his own interests and neglecting the care he owes to himself? […] Each of us puts his person and all his power in common under the supreme direction of the general will, and, in our corporate capacity, we receive each member as an indivisible part of the whole. This act of association instantly replaces the individual person status of each contracting party by a moral and collective body, composed of as many members as the assembly has voice and receiving from this act its unity, its common identity, its life and its will.”

-Jean Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract

In this passage, Rousseau asserts that, because each individual contributes their free will to the collective, even if the outcome of the collective’s will differs from his own, he is still served by that collective. A Citizen in this context would submit himself to the will of the People, but the knowledge that each and every Citizen must also submit himself to that same general will gives the People the power of unanimity, even if there is disagreement among them.

In a utopia, a perfect balance would be struck between the Citizen’s rights and the State’s power, and society would flourish. Unfortunately, history has shown that this balance is nearly impossible to achieve. As Rousseau states:

“Just as the individual will is constantly acting in opposition to the general will, so the government is continually exerting itself against the [Citizen]. The more strenuously it does this, the more the constitution changes; and because in this situation there’s no other corporate will to create an equilibrium by resisting the will of the [State], eventually the [State] will bear down hard on the [Citizen] and break the social treaty. This is the inherent and inevitable defect which, from the very birth of the body politic, tends ceaselessly to destroy it, as age and death eventually destroy the human body.”

-Jean Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract

When the Social Contract fails, it is often because the State assumes that rights given to them by the Citizen become the property of the State. The Citizen, misunderstanding their relationship to the State, learns to conflate their access to rights with their governing body. This gives incentive to the State to pass stricter policies regarding the Citizen’s access to those rights. The onus then falls on the Citizen to maintain the agreement, giving more and receiving less in return. In layman’s terms, when the people give power to the government, the government does not give it back willingly.

What is the role of the State?

Brazil, like 1984, is a depiction of a totalitarian government where the State is noticeably absent. Though almost every character in the film is a government employee of some sort, we never get the sense that any one of them has any control over their position. However, unlike 1984, there is no Big Brother, and this creates an illusion of a self-governing society. Because we do not see a character in power, a Great Dictator, if you will, on the surface, it may even look as though each character is acting as a free agent. After all, Brazil’s government is made up of the common collective, the total will of the people as outlined by Rousseau, a self-imposed and self-sustaining bureaucracy.

It is important to keep in mind that Rousseau actually discouraged this type of government due to its potential to be twisted by deception:

“It follows from all this that the general will is always in the right and always works for the public good; but it doesn’t follow that the people’s deliberations are always equally correct. Our will is always for our own good, but we don’t always see what that is; the populace is never corrupted, but it is often deceived, and then—but only then—it seems to will something bad.”

-Jean Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract

Rousseau did not believe that the people should directly govern themselves. In fact, he argued that the more the Citizen became involved in the affairs of the State, the less effective and more partial the State would become.

“Now, the total force of the government is always that of the state, so it doesn’t vary; from which it follows that the more of this force the government spends on its own members the less it has left to employ on the whole people. Thus, the more magistrates there are, the weaker the government is. […] Also, it’s certain that the more people are put in charge of some project, the longer it takes to get it going; that in giving too much weight to prudence one doesn’t make enough allowance for the possibility of good luck; and that with too many people involved an opportunity may be let slip so that all this deliberation results in the loss of the goal that the deliberation was about.”

-Jean Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract

It would be ridiculous for anyone in the world of Brazil to ask to speak to the “Man in Charge”. The inevitable response would be, “The man in charge of what? Which department? Do you have the proper form?” And it would be heresy to ask, “Why do we do things this way?” The answer, if you received one at all, would certainly be, “That’s the way it is done.”

This is central to the breakdown of free will that we see in the dystopia of Brazil. In the film, almost every single character is a government employee, and those who aren’t government workers are heavily regulated. This creates a nightmarish bureaucracy: ineffective, but brutal.

The illusory power vacuum of bureaucracy creates confusion for its Citizens. The State takes advantage of this confusion to exert more and more power over the Citizen until they become overwhelmed and submit themselves wholly to the will of the State.

As Rousseau states in The Social Contract:

“If then the populace promises simply to obey, by that very act it dissolves itself and loses what makes it a people; the moment a master exists, there is no longer a sovereign, and from that moment the body politic has ceased to exist.”

There is no free will in Brazil. There is only the comfortable illusion of choice, a deception that has been adopted by the people for the sake of self-preservation. Characters have no freedom to enact change, leaving them no choice but to continue to sustain the system that feeds upon them.

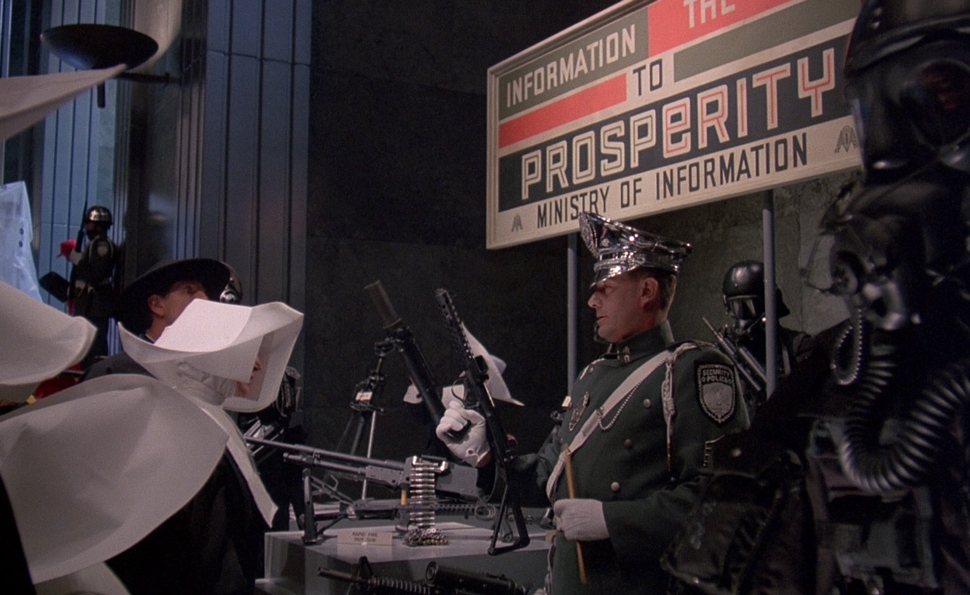

The State may not be visible, but it is definitely present and almost certainly malevolent. In the film, Mr. Helpmann, the Deputy Minister of Information, takes on the role of State. He serves very little purpose to the plot (unlike Jack Lint, Sam’s surgeon friend). Thus we can assume that he is a proxy, acting as the personification of the antagonism the system itself represents.

Mr. Helpmann is not in charge, but he speaks for those in charge. Either that, or he speaks on behalf of the nebulous status quo. In a way, this prospect is even more terrifying. After all, evil without form and substance would be impossible to fight.

In a broader sense, the State may be represented by the characters of Spoor and Dowser. Spoor and Dowser are government-contracted air conditioning repairmen. When Sam’s air conditioning unit breaks, he calls emergency services to try to get the unit fixed. A recorded message tells him that emergency services does not operate between 11:00PM and 9:00AM. Desperate for a solution, he accepts the help of rogue air conditioning repairman Harry Tuttle. Tuttle fixes the air conditioning unit with an illegal part, and all seems well.

Unfortunately, emergency services actually does send two repairmen named Spoor and Dowser to deal with the unit, but they show very little interest in actually fixing it. Spoor and Dowser are immediately suspicious when Sam lies and tells them that the unit fixed itself. They in turn dedicate their efforts to discovering the illegal part and reporting Sam for his fraternization with Tuttle, making no effort to aid Sam in any way.

Spoor and Dowser then systematically and invasively tear apart Sam’s apartment, leaving a labyrinth of loose pipes, ducts, and wires dangling from the walls and ceiling, the entire place filled with smoke and rubble. When Sam asks them to clean up the mess, they gleefully evict him from his apartment. (It is important to remember that air conditioning repair is not privatized in the world of Brazil. In our world, it would be the equivalent of two firefighters forcefully breaking into your home, tearing apart all of your wiring and plumbing, accusing you of committing crimes, and then kicking you out onto the street.)

This sequence of events tells us some very important information about the role of State in Brazil’s society:

1) The State feels no responsibility to help its citizens, even if they are in peril.

2) The State’s main concern when dealing with its citizens is crushing any possible criminal activity, no matter how minor the lawbreaking may be.

3) The State is suspicious and actively hostile to all citizens because citizens are always presumed guilty.

4) Any proof that the State is not perfect is considered taboo; therefore, any citizen who attempts to report a flaw with the status quo becomes an enemy of the State.

What Is The Role Of The Citizen?

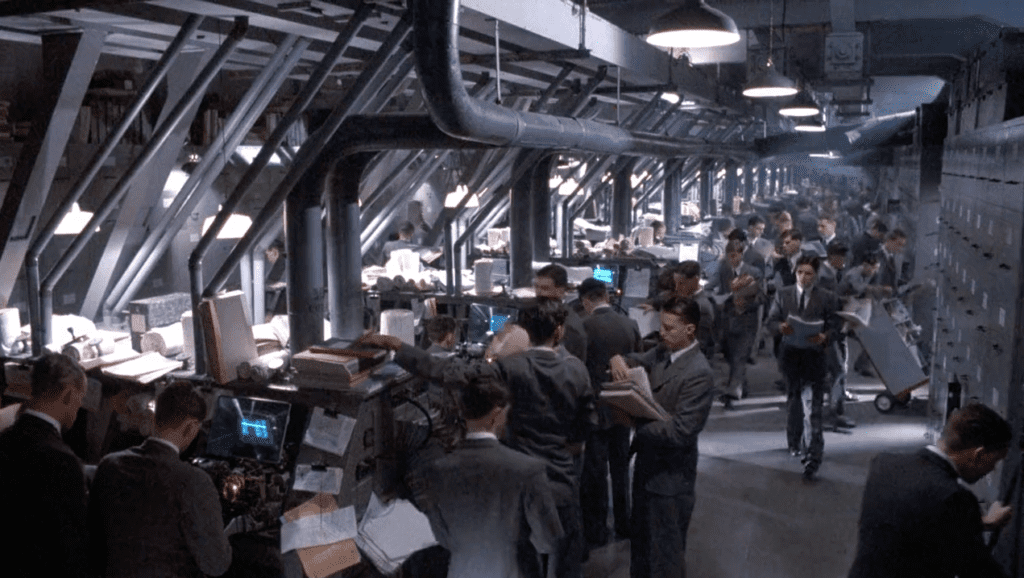

Harvey Lime is one of the most fascinating additions to Brazil’s colorful cast of characters. Lime works in Information Retrieval, and he shares a wall (and a desk) with Sam, as we see in this humorous scene.

Lime is interesting because he seems to be a model employee. He shows up to work every day and never seems to cause any trouble. However, as far as we, the viewer, can tell, Lime never actually does any work. Harvey Lime claims that computers are his specialty, but we quickly discover that he doesn’t actually know how to use his computer. In fact, he doesn’t even know how to turn it on.

In the real world, Lime would have been fired from his job, but in Brazil, Lime is a model citizen. This is because the bureaucratic government in Brazil is so full of redundancies that most citizens are only expected to look like they are working. As long as citizens effectively look effective, their actual effectiveness is incidental. More important than usefulness is the ability to blend in. Since a mistake might make Lime stand out, he chooses to do nothing. In the world of Brazil, doing nothing is always preferable to the possibility of doing the wrong thing.

Jack Lint is the perfect Citizen. He is a surgeon, employed by the government as an interrogator. On the surface, he seems friendly and approachable, but Jack’s demeanor is off-putting. He seems relaxed amidst the chaos of the overbearing and disorganized totalitarian government, and is chillingly cavalier about the deaths of innocent people. Jack has a wife and three children, but he treats them as if they are incidental. When Sam comes to Jack asking for help, Jack says, “We’ve always been close, haven’t we? Well, until this whole thing blows over, just stay away from me.”

In Brazil, most citizens survive by blending in and doing as little as possible. Jack’s confidence and relative position of power sets him apart. Jack is not surviving; he is thriving. As the film progresses, it becomes clear that Jack’s intentions are sinister. The message here is clear: The perfect Citizen is a monster.

What Purpose Does The Hero Serve?

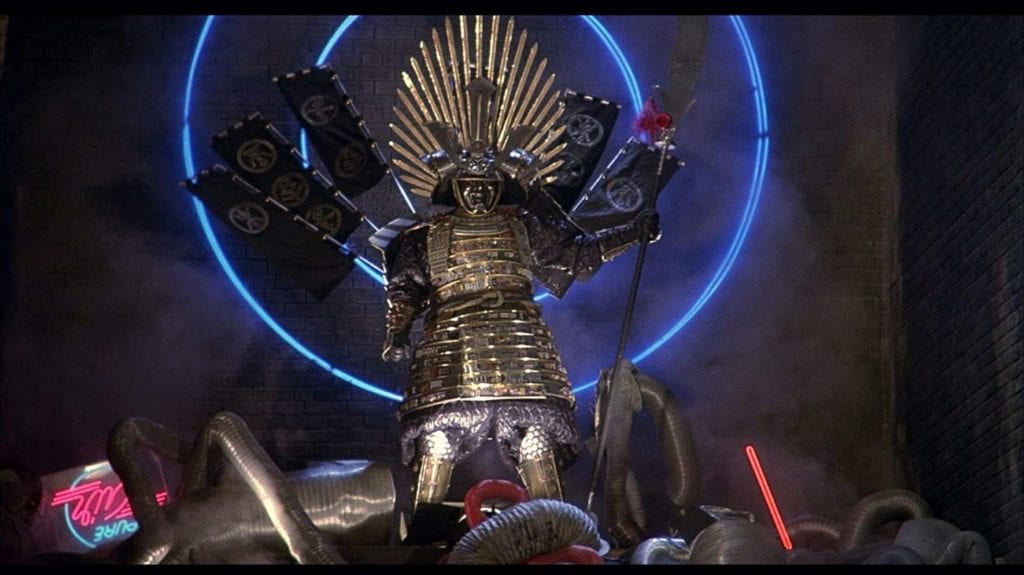

Our hero is not notable due to his strength or intelligence, but in his ability to daydream. Sam exemplifies everything that the government tries to suppress. He displays creativity when he is able to help his friend and boss Mr. Kurtzmann think of solutions to a problematic typo. He shows the ability to improvise numerous times, but most notable is the moment when he jerry-rigs a mail contraption to feed back into itself. This is an act that aligns him thematically with the likable renegade Harry Tuttle.

On the surface, Sam is a passive hero. He does not do much to influence the world around him. In fact, the movie seems to blow past him, sometimes literally, as in the scene when he begins work at Information Retrieval.

Sam does not advance the plot in any meaningful way, but I would argue that this lends credibility to Brazil’s world. It is important to keep in mind that this character exists within the confines of a totalitarian regime. He is not a freedom fighter. Although considering the dearth of freedom in this world, any act in opposition to the status quo is an act of rebellion. Like Winston in 1984, Sam is defined by the government that controls him. Therefore, his rebellion is more symbolic than literal.

Sam does not change anyone’s life for the better, at least not in the long run. He is, from an outside perspective, completely unremarkable. Even Sam’s mother only shows him cursory interest. In fact, it is unlikely that anyone in the universe of Brazil would even remember Sam’s name if he died.

That being said, it isn’t fair to judge a hero based on his effectiveness alone, especially when he is placed in opposition to a totalitarian regime. Katniss Everdeen from The Hunger Games would fall very short as a hero if we only analyzed her overall contribution to the rebellion.

In 1984, any good deed Winston performs is negligible when compared to the harm he causes. Even Rick from The Walking Dead probably destroys more lives than he actually saves. The power fantasies of dystopian films like V for Vendetta or Dark City, by contrast, are much more satisfying, but they do not hold up as well to scrutiny.

What is important in these dystopian scenarios is the struggle itself. Sam’s contribution to the resistance is negligible as his only real goals are to free his own mind from the control of the government and save Jill. It is the struggle itself that ennobles him, not the scope of his accomplishments. In a world where free will is an illusion, where right and wrong are clouded in a fog of fear and confusion, Sam chooses to do the right thing. This makes him a hero.

(It is important to note, however, that Sam’s heroism does not absolve him of guilt. After all, he was a willing participant in the oppressive system and only rebelled when that system turned against him.)

How did Brazil’s bureaucracy become a dystopia?

Some might see Brazil as an indictment of communism due to the perceived “equality” of the citizens and the lack of an elected ruling body. This belief does not hold much weight upon examination of the social interactions in the film. Hyper-capitalism is the clear villain of the piece. In one notable scene, the camera pans over a crowded neon nightmare of a shopping center as a young child asks Santa for a credit card. Later, this line, spoken by a police officer, is particularly damning: “Don’t fight it son. Confess quickly! If you hold out too long you could jeopardize your credit rating.”

Gilliam’s distaste for hyper-capitalism manifests when Mr. Helpmann, the State’s proxy, consistently refers to political insurrection in terms of a game. Mr. Helpmann speaks almost entirely in sports analogies, casting the government as the “winner” and insurrectionists as the “losers”. Helpmann asserts that life is a zero-sum game where cooperation is to be discouraged for the sake of “healthy” competition. He says this of the ubiquitous terrorists that regularly bomb the city: “Bad sportsmanship. A ruthless minority of people seem to have forgotten good old-fashioned virtues. They just can’t stand seeing the other fellow win. If these people would just play the game, they’d get a lot more out of life.”

Helpmann believes that those who live in squalor choose their life of poverty, and that those who have turned to a life of violence do this, not out of desperation, but out of spite. This is representative of the “bootstraps” mentality that many hyper-capitalists adhere to the idea that, if a person or group fails, then that person or group deserves to fail. The bootstraps defense holds that systemic issues like racism, sexism, and classism are products of “bad apples” who are too lazy, stupid, or useless to succeed.

This belief creates an aristocracy of sorts, in which those with more power and money and supposed skill lead through “divine right” by virtue of their position of power. The circular reasoning goes something like this: Only those who deserve to be rich and powerful are rich and powerful. I am rich and powerful. Therefore, I deserve to be rich and powerful. In Brazil, it is clear that hyper-capitalism does not create a meritocracy, but in fact, the opposite, where those of talent and skill are squashed beneath the machinations of the ruling class.

It is the combination of bureaucracy and hyper-capitalism that causes an oppressive totalitarian regime to take hold in the world of Brazil. There is some Christian imagery in the film, but the people are not particularly religious. Instead, they worship success, youth and beauty, materialism, ambition, and most of all, money. This mentality is exemplified by Sam’s mother and her fanatical obsession with plastic surgery.

In a hyper-capitalistic society, money is God. If that rings true, then the poor are immoral. And if the poor are immoral, then the government feels no obligation to help them. Furthermore, Brazil posits that, in a bureaucracy, the government would be run like a business, and if businesses only exist to make money, then the government’s only purpose is to make money.

In Brazil’s hyper-capitalist bureaucracy, the government has no Social Contract with the people. The State is not answerable to the Citizen, but the Citizen is still bound to the rule of the State. This power imbalance creates a dystopia.

Final Thoughts

It is interesting that 1984 and Fahrenheit 451 are often called science fiction as neither of them have a clear timestamp for their setting. (The title of 1984 is intentionally misleading.) The assumption on the part of the reader is that these stories must take place in the future (and thus be science fiction) because they do not take place in the past. After all, if Fahrenheit 451 took place in the past, we would know about it. Because of this, whether or not there is visible future tech in the dystopian society, these stories are generally seen as “futuristic”.

Many directors, when adapting these works, skew toward a futuristic visual style. Others, like Gilliam, choose a mish-mash of many different styles and time period indicators to give the audience a feeling of past, present, and future. This lends a timelessness to the piece that serves it well.

Brazil is raw and stirring. The production design is fascinatingly complex and eerily hollow. The direction is frenetic, and the camerawork is bizarre and effective. Brazil was released in 1985, which was a year ruled by Thatcherism and Reaganomics. It is definitely a product of its time.

In the year 2019, in the wake of Trump and Brexit, this film feels downright prophetic. History repeats itself, and as long as people crave money and governments crave power, Brazil will remain relevant.