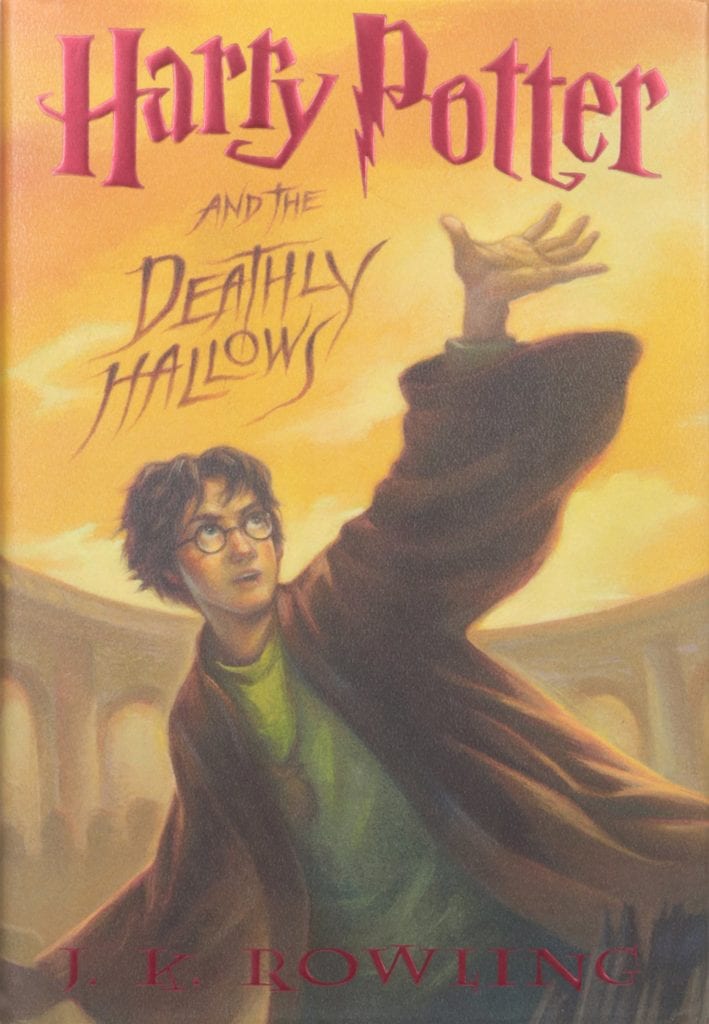

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows was published in 2007. It is the last book of J.K. Rowling’s epic seven-part adventure revolving around her hero, Harry Potter. Copies of the novel were reserved months in advance, and local bookstores hosted all-night costume parties for the book’s release. The attendees of these events were of all ages, desperate to finally get their hands on possibly the most anticipated book in history. I was eighteen years old when Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows was released, and waited all night at Borders Bookstore for a copy. At 11:59PM on July 20th, 2007, the biggest question on everyone’s mind was: Will Harry Potter die?

Stranger than Fiction is a 2006 film directed by Marc Forster. It stars Emma Thompson as Karen Eiffel, a well-regarded author struggling to finish her latest book, Death and Taxes. Eiffel is famous for killing off her main characters in poetic and harshly ironic ways, but she grapples with writer’s block when it comes to killing her latest protagonist, Harold Crick, played by Will Ferrell. After much speculation and struggle, Eiffel eventually devises the perfect tragic end for her hero. However, when Harold comes to her to plead for his life, Eiffel is shaken to the core by the realization that her characters are real. She must ask herself a very important question: Is her greatest masterpiece worth Harold’s life?

In this discussion of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, we will talk about the controversial ending to the Harry Potter series through the lens of Stranger than Fiction. This is not strictly an analysis. Instead, it will be more personal, focusing on my relationship with Harry Potter and the expectations placed on J.K. Rowling by the fans, including myself.

Warning: This analysis contains spoilers for Stranger than Fiction and Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.

Why is the ending to Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows controversial?

Let’s get this out of the way right now – I don’t like the epilogue of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, and I am not alone in that opinion. But what was it that rubbed so many fans the wrong way? I always pointed to the sappiness of the ending, and Rowling’s insistence that all of the characters were happy and leading perfectly normal lives felt like a betrayal. It was as if Rowling was unable or unwilling to admit to the damage that she’d inflicted on her own characters. Harry Potter saved Hogwarts, but it was at the cost of himself… or, it should have been. A lot of readers felt that Rowling was trying to have her cake and eat it too.

In the 2007 documentary J.K. Rowling: A Year in the Life, Rowling defended the epilogue of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows:

“I felt it would be a betrayal of the character if I showed Harry doing anything other than living what, all along, he has discovered to be true, which is that love is the strongest power there is. And I thought a lot about people who have been through terrible things, like wars, and having to come home and rebuild and espouse normality after seeing horrors. That’s always seemed to me to be such a courageous thing to do. And climbing back to normality after trauma… it’s much, much harder to rebuild than to destroy.”

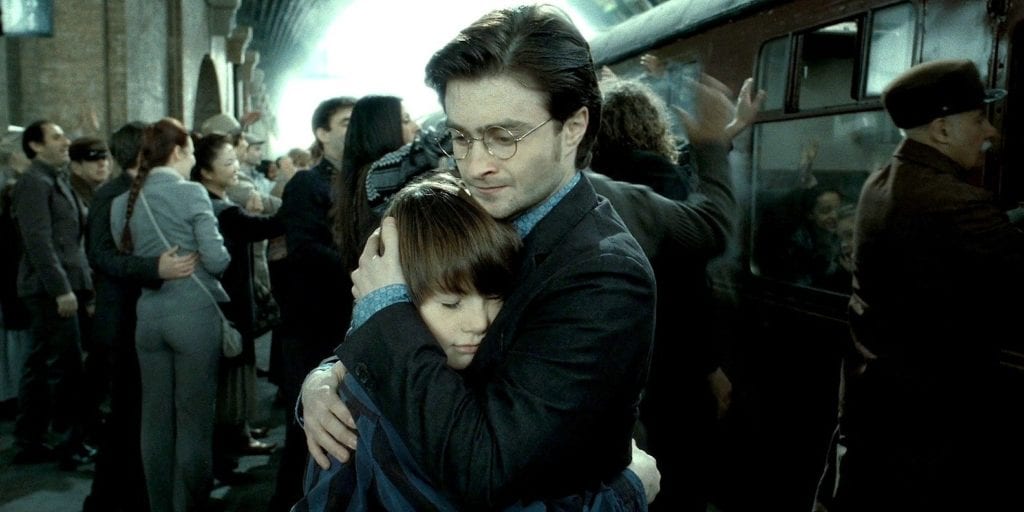

While I applaud the intention of her ending, I cannot condone the text as written. There is no trace of Harry Potter’s hardships in the epilogue. There is no hint that Harry is anything other than blissfully happy, working as an Auror, married to his high school sweetheart, kissing two of his children goodbye as they board the Hogwarts express. Seeing Ron and Hermione seem equally content and well-adjusted despite their collective hardship, my suspension of disbelief was stretched beyond its breaking point. Everything about the resolution of these characters rang false.

The issues don’t stop there. As a fan, I was unsatisfied with Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows long before the epilogue. I felt that the pacing was all over the place, trundling along at a tedious pace for the first half of the book and then plummeting head first into the ending with no breathing room whatsoever. It felt as if Rowling could not figure out whether she wanted to keep writing the last book forever, or wanted it over and done with as quickly as possible.

More than the epilogue, I was disappointed with the climax of the story. In the final battle, the culminating moment of seventeen years of strife, Harry Potter heroically defeats Voldemort by lecturing him on the laws of wand ownership.

Now, if this idea had been set up earlier in the series, the payoff might have worked. After all, most of Rowling’s important plot devices are introduced long before they are relevant to the story. The Vanishing Cabinet is introduced in book 2 (and comes into play in book 6), the two-way mirror is introduced in book 5 (and comes into play in book 7), the twin cores are introduced in book 1 (and comes into play in book 4), Rowena Ravenclaw’s diadem is introduced in book 6 (and comes into play in book 7), and so on.

The books are full of Easter eggs that pay off throughout the series, but the obscure laws revolving around the intricacies of wand ownership? That concept is not even brought up until the beginning of the 7th book, and that is simply not enough time for the reader to become comfortable with such a convoluted concept. In fact, throughout most of the series, wands seem to be, for the most part, interchangeable. Sirius has no trouble using a borrowed wand in book 3 (and every subsequent book), nor does Barty Crouch Jr. in book 4. The whole thing comes across as clumsy and confusing, which is especially frustrating when the entire climax hinges on the readers’ understanding of it.

Needless to say, I was disappointed with Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. And part of me, a part of me that I’m embarrassed to admit to, was genuinely angry.

So what was the right way to end Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows?

“Harold, I’m sorry. You have to die. It’s her masterpiece. It’s possibly the most important novel in her already stunning career, and it’s absolutely no good unless you die at the end.”

–Professor Jules Hilbert, Stranger Than Fiction

Many alternate endings to the Harry Potter series have been put forth over the last twelve years, and most of them have merit. I’m going to share the ending that I would have liked to see:

Harry Potter learns the truth about Dumbledore’s plan to defeat Voldemort. After instructing Neville to kill Nagini, he walks into the forest. He activates the Resurrection Stone and finds strength in the love of those who have died to protect him. Harry presents himself to Voldemort, and without any ado, fully prepared to meet his end, The Boy Who Lived finally dies.

He meets Dumbledore in a King’s Cross Station of sorts. They discuss many things: Harry’s sacrifice, Dumbledore’s past, and the Deathly Hallows. Dumbledore explains that Harry’s sacrifice cast protective magic over all of his loved ones, the same protective magic that Lily had used to save Harry seventeen years prior. Satisfied in the knowledge that his family and friends will be all right, Harry boards a train and moves on.

Hagrid carries Harry’s body back to Hogwarts. The sight of Harry’s body doesn’t destroy the spirits of the fighters, as Voldemort had intended, but instead emboldens them. Neville draws the Sword of Gryffindor and destroys Nagini. Draco Malfoy turns on his master and disarms him with Expelliarmus, unknowingly claiming the Elder Wand for himself. Curses fly through the air as Death Eaters attempt to fight or escape, but each spell they cast reflects back on themselves. Voldemort takes a wand from one of his dead servants and points it at Malfoy, but with Malfoy protected by the Elder Wand and Harry’s enchantment, the killing curse rebounds, just as it did seventeen years prior, and Voldemort is destroyed.

The people ignore Voldemort’s body and rush to Harry, but he is gone. They carry him through the halls of Hogwarts in a solemn funeral procession and then bring his body back to Godric’s Hollow to be buried next to his parents.

Harry is dead, certainly, but wizards have ways around these things.

A painting of Harry is hung in the Headmaster’s Office, between Albus Dumbledore and Severus Snape. He advises the headmasters that follow, including Minerva McGonagall and Hermione Granger. Hermione is the first muggle-born to ever serve as headmaster of Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. Ron fulfills Harry’s lifelong dream and becomes an Auror. He and Hermione marry, and he visits the school often. They tell Harry all about their lives and the lives of his loved ones. They tell him how beautiful Ginny’s children are, and about their own children, including their adopted son, Teddy Lupin. While these conversations are tinged with regret, they are also joyful.

Draco retains possession of the Elder Wand, but he no longer desires power. He dies of old age, and the Elder Wand is buried with him.

The Resurrection Stone is never found and instead becomes part of the Forbidden Forest. Hagrid still visits the forest often. Not just to see Grawp but to check on the growing sapling in the clearing where Harry Potter died. Strangely, he feels at ease when he tends to the plant, and sometimes, he thinks he can feel Harry’s presence there, thanking him, loving him.

The Invisibility Cloak is given to Molly Weasley, and when she dies, she leaves it to Ginny. The cloak is passed down through the Weasley family for generations, offering protection, as well as enabling a few well-intentioned trouble-makers along the way.

Life after Harry Potter is not perfect. There is much rebuilding to be done, but the people do not feel despair. Hope prevails.

What does Harry Potter have to do with Stranger Than Fiction?

“In the grand scheme, it wouldn’t matter… No one wants to die, Harold, but eventually we do… Even if you avoid this death, another will find you, and I guarantee that it won’t be nearly as poetic or meaningful as what she’s written. I’m sorry, but it’s the nature of all tragedies, Harold. The hero dies, but the story lives on forever.”

–Professor Jules Hilbert, Stranger Than Fiction

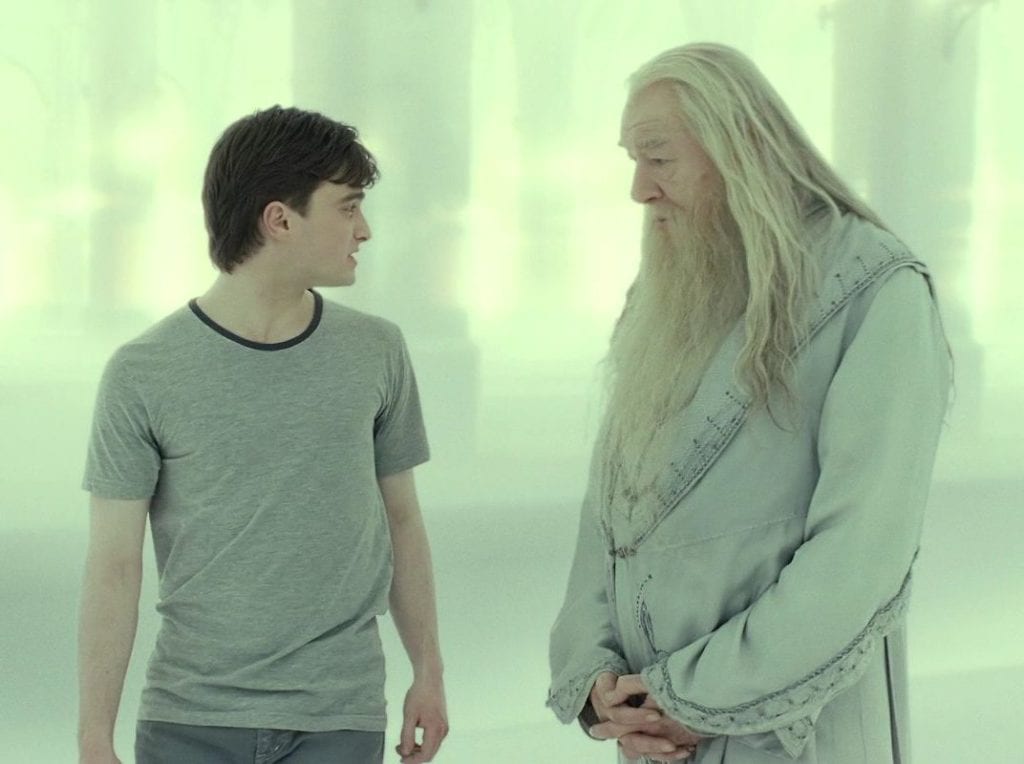

The narrative of Stranger Than Fiction revolves around Harold Crick, but the meta-narrative (the story beyond the main narrative) is centered on Karen Eiffel. The main conceit of Stranger Than Fiction is that Harold’s life is being dictated to him by an outside force, the author of the book in which he is the protagonist. This sort of framing device is rare, but not unheard of.

Moulin Rouge opens and closes with dictation from the protagonist author. Movies like Finding Neverland and Becoming Jane explore how authors’ works are influenced by events in their real lives. Atonement plays with the author as unreliable narrator. The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh even features the main character, Pooh, interacting with the narrator and asking questions about the story.

However, Stranger Than Fiction differs from all of these in one unique way: Harold Crick changes the meta-narrative. In other words, Harold Crick is real. He exists in the same exact reality as his narrator. Up until the third act, Harold may have existed in a reality separate but almost identical to the real world of Karen Eiffel, but he changes the course of his life and hers when he walks into her office and pleads for his life.

Harold says, “I mean, now, since we’ve met, and you can see that I exist, you’re not gonna kill me, right?” Eiffel’s response of “I’m sorry! I’m just trying to write a book!” might seem cold at first, but the weight of this burden shows when she recalls the cruelty with which she dispatched her previous protagonists (who may or may not have existed in the real world). Coming face-to-face with her own hero forces Eiffel to evaluate the worth of her characters’ lives, and the worth of her own. Is she a bad person for dooming so many people to such horrible fates?

While this conundrum may seem unrealistic, it actually echoes an age-old literary dispute: Should you kill your protagonist?

The answer isn’t simple. An author might kill a protagonist as a way to skip the resolution of a novel. This is generally inadvisable. Sometimes, the story is more meaningful if the protagonist dies, and an author might explore both avenues, trying out different endings to see which one feels right. Whether or not it is appropriate to kill your protagonist should be evaluated on a case by case basis with careful thought.

The question facing Karen Eiffel is slightly different. She knows that killing Harold will make for a better story. Her question is an ethical quandary rather than one of narrative craft. Can she, knowingly, kill a good and honest man for the sake of something as trivial as a story?

It’s an interesting question, and surprisingly, it’s one that comes up often for writers that specialize in book series. The longer an author and an audience spend with a character or group of characters, the more real those characters feel. For many fans, fictitious characters feel like friends, even family, and the loss of one of those characters could be devastating.

Eiffel’s struggle may be supernatural, but her crisis of conscience is real. In this way, Stranger Than Fiction mirrors J.K. Rowling’s conflicted feelings regarding the end of her beloved Harry Potter series. While watching Stranger Than Fiction, I couldn’t help but wonder, did Harry Potter visit J.K. Rowling to plead for his life too?

Why didn’t J.K. Rowling Kill Harry Potter?

In J.K. Rowling: A Year in the Life, Rowling said this about the ending to the Harry Potter series:

“Some people will loathe it, absolutely loathe it. But the thing is, that’s as it should be because, for some people to love it, others must loathe it. That’s just in the nature of the plot. Some people won’t be happy because what they wanted to happen hasn’t happened. And to an extent, there’s so much expectation from the hardcore fans that I’m not sure I could ever match up to it, but… um… I’m… well… I’m actually really, really happy with it.”

In Stranger Than Fiction, Harold seeks out the help of a literary professor, Jules Hilbert (played by Dustin Hoffman). Professor Hilbert is curious about the situation but apathetic to Harold’s plight. He is far more interested in Harold as a character than as a person. Jules Hilbert is not an evil man, but he is a fan of Eiffel’s work. It is this distinction that fuels his cruelty.

Jules Hilbert cares more about the story than the well-being of Harold and the author he claims to love so much. For him, Harold is a character first and a person second; Karen Eiffel is an author first and a person second. When Harold gives Professor Hilbert a copy of Eiffel’s unfinished novel, hoping to find some way to save himself, Hilbert assures Harold that the story can only end one way: with Harold’s death.

In the end, Harold jumps in front of a bus to save a little boy, offering himself up to his ultimate fate, much in the way Harry does when he gives himself to Lord Voldemort to save his friends. It is these selfless acts that save the lives of Harold Crick and Harry Potter.

In the final scene, Eiffel visits Jules Hilbert and asks him to read her new ending to the novel. He tells her, “It’s okay. It’s not bad. It’s not the most amazing piece of literature in several years, but it’s okay,” and she responds, “You know, I think I’m fine with okay.”

Karen Eiffel is a human being, not a divine messenger. She is an author trying to write the best story she can. But she met Harold, and she fell in love with him, not romantically, but maternally. She is his creator, and she knows every struggle, every thought, every boring detail of Harold Crick’s ordinary but miraculous life. When Harold knowingly sacrifices himself to save a child, he becomes not only her creation, but her hero.

When asked about the ending to the Harry Potter series, J.K. Rowling said:

“In some ways, it would have been a neater ending to kill him, but I thought it would have been a betrayal because I wanted my hero (and he is my hero) to do what I think is the most noble things, so he came back from war, and he tried to build a better world…”

Similarly, when Jules Hilbert asks Eiffel why she changed the ending, she says:

“Because it’s a book about a man who doesn’t know he’s about to die and then dies. But if the man does know he’s going to die and dies anyway, dies willingly, knowing he could stop it, then isn’t that the type of man you want to keep alive?”

Jules Hilbert, like the fans, cares more about the product, the masterpiece, than the life of a single character. And he may not be wrong. As he says: “The hero dies, but the story lives on forever.” But while the craft of writing is arguably objective, the worth of the art is subjective. Therefore, Eiffel’s position is fair too. To her, Harold’s life is worth more than her masterpiece, and because she is the author, it is her decision to make.

J.K. Rowling knew Harry Potter long before we did, and for a long time, he was hers alone. Yes, once a novel is published, it belongs to the readers as much as the author, but it helps to remember that Rowling is a human being. Perhaps, for her own peace of mind, she simply couldn’t end the series without knowing that Harry was going to be okay.

Rowling is not just the author. She is Dumbledore, she is Lupin, she is Lily and James, she is Sirius, she is Ron and Hermione, and she is Harry. She is mother and mentor, guiding force and deity, all in one. When Snape judges Dumbledore for raising Harry like a lamb to be slaughtered, Dumbledore has no objections to this accusation. It’s clear that he suffers immense guilt for his part in Harry’s demise. Would Rowling be any different if she let Harry Potter die? Could she live with herself if even Snape would find her actions reprehensible?

When asked how she wanted to be remembered, Rowling simply said, “As someone who did the best she could with the talent she had.”

So, again…

What is the right way to end Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows?

The answer: There isn’t one. There is no “right way” to end any book. We have only what is written. It may be imperfect. It may even be disappointing. But the story is over, and it cannot be changed. Even if it could be changed, SHOULD it be? Rowling had every right to end her story the way that she wanted.

So, thanks to Stranger Than Fiction, over ten years after the release of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, I am ready to forgive J.K. Rowling. More importantly, I am ready to ask for forgiveness for my selfishness as a reader.

I think, perhaps, Rowling was right. Harry Potter is not just a character in a book. He’s not literary theory. He’s my friend. Though I’ll never like the epilogue, though I’ve re-written the ending a thousand times in my head, I must admit that I’m happy Harry Potter is alive.